A childhood crush propelled a local filmmaker to achieve groundbreaking storytelling in New Zealand cinema three decades later.

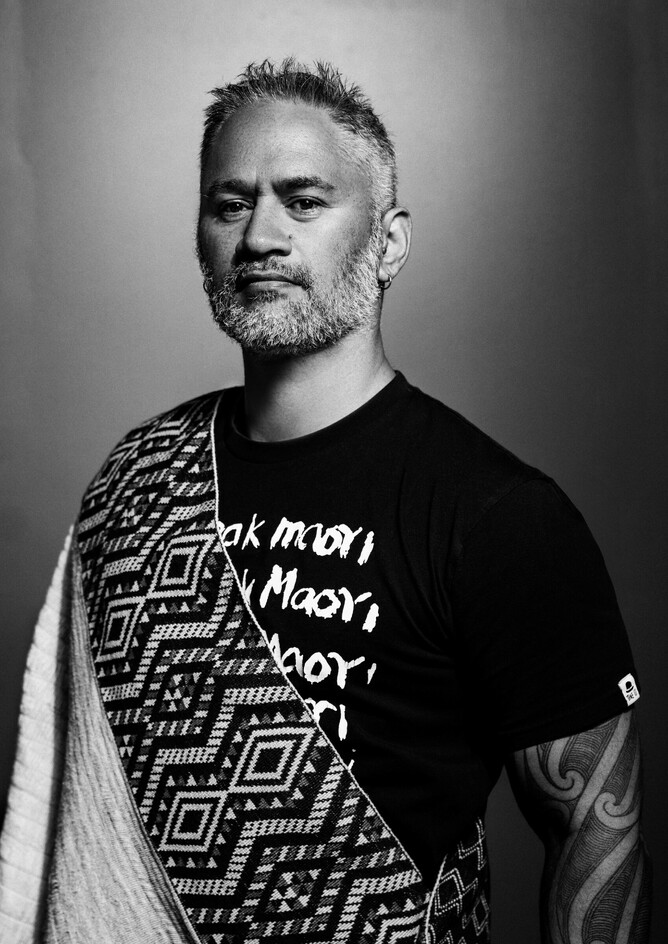

Director Mike Jonathan (Te Arawa, Tainui, Mātaatua) grew up in Taumarunui and remembers his mother taking him to the movies to watch Utu when he was nine.

“Utu blew my mind because I saw Māori people on the big screen. A lot of them were getting killed, and it made me really emotional at the time.

“I fell in love with Merata Mita because of her moko kauae; she looked amazing. I had a big crush on her for ages. That film was the catalyst for me becoming a filmmaker. I watched it and told myself that I wanted to make movies to do what it did to me – to inspire people and show our culture and lots of beautiful brown people on screen. It was always my drawcard into the industry,” says Mike.

After high school, Mike applied for a Commercial Design course at Waiariki Polytechnic (now Toi Ohomai) in Rotorua, where he tried his hand at drawing, painting, photography, and video. During this time, he teamed up with Te Karere reporter Martin Rakuraku, and not long after, he secured a job at Cardno Video Productions.

“I was allowed to train as as a cameraman and cut my teeth. From then on, I just learned as much as I could. Within a couple of years, people were calling on me, and there was this transition of people calling this Māori boy,” says Mike.

During his formative years in Rotorua, Mike did not have a strong command of the reo, but he recognised its significance. His collaboration with Martin was a pivotal moment. Despite his limited knowledge, he found himself engaging in te reo conversations. This stepping stone drove him to pursue further courses, deepening his understanding. It began his mission to infuse te reo and iwi Māori into his work, a journey of cultural representation in cinema.

“I started Hula Haka Productions in Rotorua with my then-partner, Nevak and best mate Glen Bates. Within six months, we had 16 people working for us, and things were crazy. Māori TV had kicked off, and we had a flagship show called Marae DIY, which has renovated 150 marae nationwide. But I always wanted to get into film.”

In 2005, he paired up with his friend Tere Harrison to direct the film she had written about a young girl growing up in Wellington in the 1980s, called Hawaiki. It was also the start for another great friend, Libby Hakaraia.

“Hawaiki is a beautiful film and was the start of my career in making narrative stories. I made another film, Shadows, a form of expression at the time, dealing with personal demons and making them into literal ones. After that, I experimented and worked on other people’s shows and films. We did Taika Waititi’s Boy, but I always knew that I wanted to make a film,” he says.

In 2007, Mike was contacted by Merita Mita.

“My film crush called me up and said, ‘Hey, come hang out for a little bit’. She was a huge deal to me in becoming a filmmaker and always pushed me to tell the story from the right perspective.

“A lot of Merita’s films are so raw, and she did things no one had ever done. That’s why she’s known as a pioneer in indigenous films. She went to Hawaii, North America, and Canada to help inspire Indigenous people to make films and documentaries. She did the same with me and a whole bunch of Māori filmmakers, like Taika, Te Arepa Kahi, Chelsea Winstanley, Desray Armstrong, Cliff Curtis, and many others.

“She mentored all of us to say, ‘do it from our perspective. Don’t listen to what they say. Just keep going, keep going, keep going.’ I always took that onboard and said, ‘I’m going to do it’, and years later, I’ve bloody done it. I’ve made my first film.”

Mike says that making a feature film is the ultimate achievement for a director. As the director, he has control over every creative aspect of the film: assembling the right team for costumes, production design, props, and camera work; choosing the right techniques and colour palette; overseeing everything visual and auditory, including the score and every other element to ensure the film resonates with everyone.

“I started Ka Whawhai Tonu eight years ago. But simultaneously, it has been a 41-year journey – since I was nine years old watching Utu. It’s a part of that because I always wanted to make a film that meant something to me, not just see if it flies.

“I wanted to make something that meant something for us as Māori but also something for people to be educated on what happened in our past and stay true to the narratives of our iwi and whānau to teach everyone.

“This is just one of the 50 or 60 battles in New Zealand where they slaughtered us, so where do we go from here? I’ve got whakapapa in Ōrākau. Many of us have blood spilled on that land, and it’s an absolute honour to tell those stories from that perspective. Come watch this film, feel, and get inspired, and let’s have a couple of conversations on how we move this land forward.

“It may be naive of me to think that I can make change through a film, but Merita always believed in it,” he says.

Mike gets emotional when he expresses his appreciation to everyone who helped make his vision, Ka Whawhai Tonu, a reality.

“I come from a place where I never wanted to say that I was proud of my work because I was too shy. But I’ve learned now from so many people to just say, ‘Thank you. I am proud of this film’.

“I’m proud of my team; I’m proud of my whānau. Everyone. Temuera. The performance he gave – I’ve never seen him perform like that. It’s the best performance he’s ever given. In Once Were Warriors, he was amazing for the time, but this one’s different. I think it’s because of his age. He’s a rangatira, and you can see it in the film. He has that presence and calmness, and he really owns it. He really embodies his character, Rewi. It’s beautiful. I’m really proud of the kids. Only one of them has trained, our main boy Paku Fernandez, but all the rest are raw and amazing.

“It’s proof that we can make our stories our own way and find success within the teams. Ka Whawhai Tonu is a $7.5 million dollar film. The Film Commission laughed at us and said you cannot do this on that money. All we could say was, ‘Just watch us do this’. We’ve been in this industry for a long time; we’ve got a lot of resources. I think we smashed it.”

But where to from here? Mike says they need to get people to invest in their films and stories, which has to be substantial funding.

“I want to do Sci-Fi, and one day, I want to make a zombie film. That’d be cool. I’ve loved zombies since I was a kid. The other holy grail is to do a Māori Battalion story, but that means going to Europe and taking the whole team there, which requires big money. If we can attract those big investors off the back of Ka Whawhai Tonu, that would be awesome. But again, it means consultation with whānau to find a way forward for all of us.

“It has been difficult to get money out of iwi because I keep telling them we need to invest in our stories, and it has to be a part of the strategy from now on. It doesn’t need to be a huge investment. It needs to be a partnership where we can break down some barriers together.

“All my iwi, hapū, and whānau really engaged once they saw a concrete concept: the trailer. When they saw the trailer, they said, ‘Okay, we’ll help you.’ But by then, it was actually too late. We need the money upfront, basically. I think we’ve proved ourselves and more and are willing to bring in a whole team of new filmmakers. This is a legacy project to share and bring them forward so they can also tell their stories.”

And every day, Mike drives past the three-storey mural of Mereta Mita on Eruera Street, blows her a kiss, and says, ‘Thank you, I’ve done it.’

Ka Whawhai Tonu opens in cinemas around Aotearoa on Thursday, June 27. In addition to the set sessions, groups can request their own.